Learning how to speak Spanish, or any language for that matter is a tremendous task.

Bilingual volleyball game!

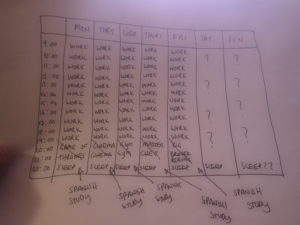

Our previous blog entries have attempted to mount the argument that learning a language is a holistic approach, and that there is no one single way of going about it. We’ve briefly introduced the materials, we’ve started to look at a program and some methods – learning vocabulary, tackling grammar and to a degree, writing. Still, we’re only halfway there, and I can say without any doubt that getting out there and speaking spanish, alongside writing, is the single most important thing you can do. Welcome to the latest entry on how to divide your study time throughout the week!

Why learning how to Speak Spanish is the Most Important thing

So why is speaking the most important thing to do? Because when you sit there and listen to the teacher rattle on, or when you sit there half taking in your online lesson on youtube, you’re only partially taking in what it is you’re supposed to be doing or learning. Don’t get me wrong, teachers are good guides and mentors, and listening to online tutorials and instructions that have some great advice or explanation on a grammatical topic can be amazing. However, what it ultimately comes down to is ‘workshopping’.

If you had to learn how to do a new job, what would be the best way to learn the ropes? Would you watch an instructional video? Would you look at a diagram? Would you read up on it? Would you let someone tell you or show you how to do it? All of those things serve a purpose, and they count, but first and foremost, the number one thing which will enable you to commit your tasks to memory is the actual process of doing it. Do you guys hold down professional jobs? Do you play a musical instrument? Are you a great sports person? Language learning is no different.

Bringing this Scenario back to the World of Learning a Language…

Everything we mentioned before about holding down a job, sports training, and pretty much every other pursuit involves watching videos and diagrams, reading instructions and listening to the experts etc. In the world of second languages, this translates to reading explanations from your books, and listening to your teacher or any number of instructional videos found online (as well as other) resources. Again, these are great, but the process of actually doing it, i.e. the most important part, comes from you. In the context of language-learning, this takes the shape of writing and speaking.

Not convinced? “Why writing and speaking? Why not reading? Why can’t I listen to a podcast or watch my favourite film in Spanish?” you ask. Well, you can. Those things are fun to do, and they serve a purpose, but to learn anything major from reading will require you to read huge volumes of materials. That’s great if you already have a great level of Spanish, but you might not. The other problem with reading, is that it’s similar to listening, in that it is often a passive activity. If you had to learn how to say something in Spanish, which would be the best way? Would you try an retain it by hearing it from someone? Would you read it, memorise it and then store it away for later use? Well, sort of.

How Many of us Remember…

…revising for exams in high school and university? You took lecture notes, right?

Many of us remember that rather than just reading something, noting it down is far more effective. Likewise, hearing something is fine, but what works better is actually listening to and engaging with someone in a situation where you are required to respond and contribute to the conversation. Speaking and writing force you to think in Spanish. You are effectively rewiring your neural pathways to function in ways that were previously not possible. You are creating new reflexes, new skills, new everything. Yeah, it’s hard work, and you’ll feel like you’ve run a gauntlet after a study or conversation session. You may feel as though you need to take a break every once in a while, but you know that it’s working…

Programming your Time…

I digress…this post is about speaking Spanish, and allocating at least an hour at some point in the week as part of a fixed study regimen. Let’s cover some ways that you might go about practising your speaking skills. There are plenty to choose from!

- Spend an hour speaking with another student or go on Gumtree or some other site and look for a conversational partner. Do half an hour in English and half an hour in Spanish or be selfish and just speak Spanish. However, don’t just speak for an hour in English because your Spanish is ‘bad’ or you’re nervous. If you don’t speak Spanish, you will have achieved nothing other than ensuring the other person walks away speaking better English.

- Join a language group and just speak Spanish for an hour. Bring a list of conversational questions and some bottles of wine to get things flowing. Most of the groups which run these types of sessions are free. Here’s one that we run, called ‘Language Swap: English/Spanish’. Not the most original name, but I didn’t come up with it!

- Hire a private tutor and do a one-on-one session for an hour or more. It’s totally up to you, and there are plenty of tutors out there who will tailor the classes to the sorts of things you want, and who are flexible with times.

- Make Spanish-speaking friends in hobby groups, language swaps, etc. Maintain contact with them and see if you can get into a routine of speaking Spanish and English, to even-out the work load and make it a more reciprocal experience.

Language exchange groups are a fun way to practise Spanish and make new friends.

Some Additional Points Regarding how to Approach Speaking

- Try to keep a notepad and pen handy. Writing down unfamiliar expressions and vocabulary will allow you to remember it more easily for next time. It will give you something to research and incorporate into another study session when you get home.

- Get your conversation partner to correct you! You can ask them me corriges por favor? (can you correct me please?)

- Most of all it’s important to remember to have a relaxed attitude when you do this. Not confident enough? Who cares!? No one cares about the mistakes that you make, but people will love the fact that you are having a go at speaking another language….and that you are determined to go further. It doesn’t matter if you make mistakes. Ever.

So that concludes a brief summary on the value of speaking Spanish – or at least trying – on a regular basis, and ensuring that it is one of the most important things in a study regimen. Next, we’ll look at a study session dedicated to writing. While you’ll get plenty of this done when you study grammar, it’s really important that you dedicate time to working on your writing skills in more of a free-style environment. This involves getting a bit creative and getting a bit social. Most importantly, in the same vein as this entry, it involves just relaxing and not being afraid to make mistakes!

Share this article!